Daniel Lubowa

INTRODUCTION:

Factors that led the ICTR’s Inception: Background Scenario

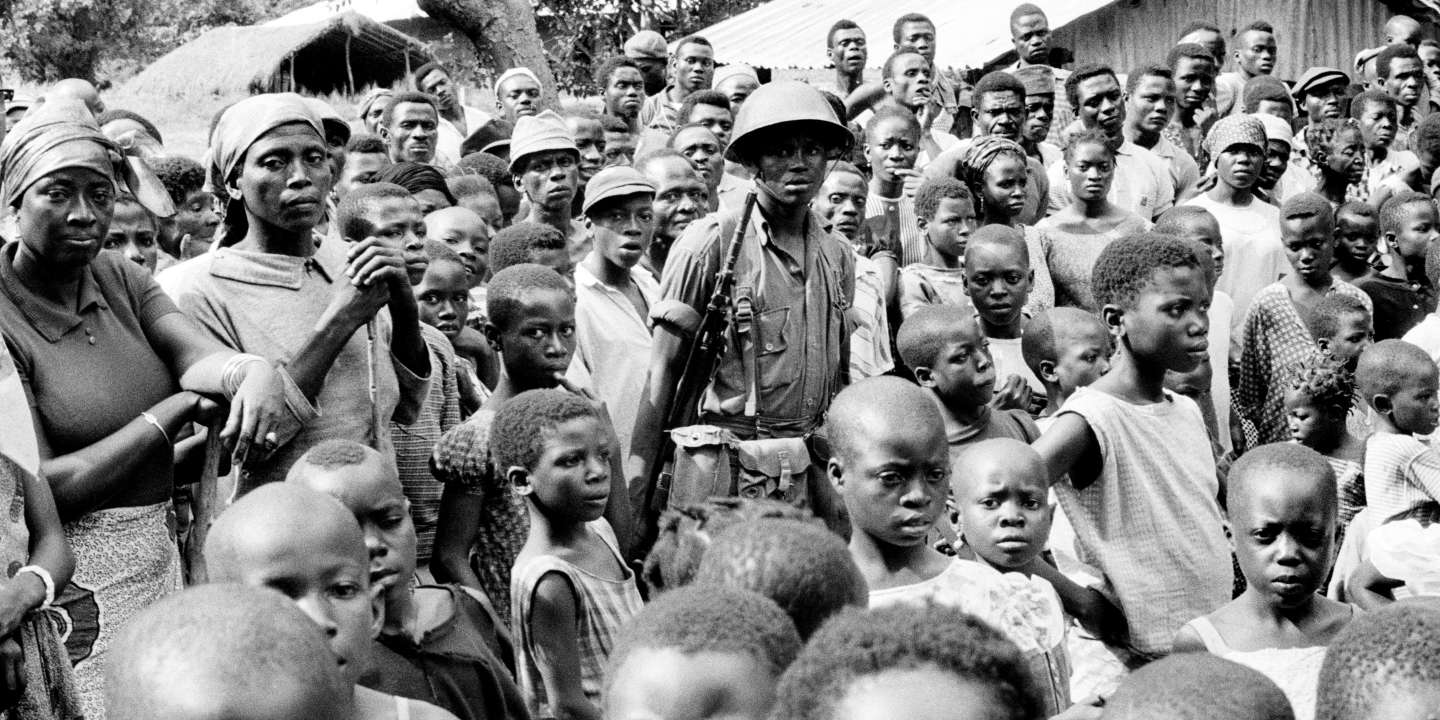

On 1st October 1990, Rwandese who had lived as refugees throughout East and central Africa since1959, when a Hutu revolution overthrew the then ruling appointed Tutsi monarchy, attacked their motherland, to return home after having tried unsuccessfully for some time to convince President JuvenalHabyarimana’s regime to allow them to return home peacefully. The war that followed hit a climax on 6th April 1994,[Gerald Prunier,1994]when President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down as it landed in Rwanda, and he was instantly killed[together with his Burundian counterpart, President Cyprien Ntarymira and several of their officers].Within hours of the announcement of the President’s death, roadblocks had been set up all over Rwanda, the hunting and slaughter that was to last three months and cause deaths of between five hundred thousand to eight hundred thousand people had started. The genocide ended only when the Rwandese Patriotic Front [RPF] resumed war and captured Kigali on 4th July 1994.By the time the civil war and genocide ended on 19th July 1994, over eight hundred thousand Rwandans had been killed[Michael P. Scharf 2018].

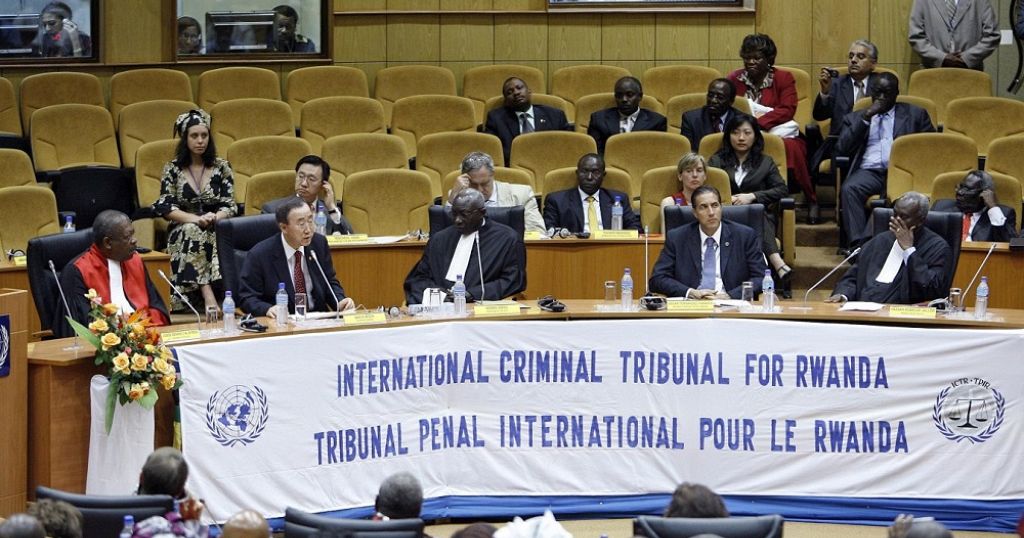

When the killings ended, it was clear that something had to be done. In an effort to punish those responsible for the genocide, the United Nations [UN] established the International Criminal tribunal for Rwanda [ICTR] to try all those responsible for genocide and other such violations committed in the neighboring states, between 1st January 1994 and December 1994.

THE ICTR: IT’S INITIAL INCEPTION: THE PROCESS

In May 1994, the United Nations Commission for Human Rights [UNCHR] met in a special session and named a special rapporteur to investigate the situation in Rwanda and instructed the High Commissioner for Human Rights [HCHR] to establish a field presence in Rwanda [Todd Howland,1998,p.106].The Rwandan Government also requested the UN Secretary General to form a tribunal to try the perpetrators of the genocide. Later, in response, the Security Council[SC] adopted the Secretary General’s report and a draft Statute for the tribunal without amendment under Security Council Resolution[SCR] 955[1994] was adopted, thereby leading to the establishment of the ICTR in Arusha, Tanzania.

THE INITIAL COMPOSITION AND STRUCTURE OF THE ICTR

The ICTR was governed by its Statute, which is annexed to SCR955[1994] consisting of three major organs; the Chambers- three trial chambers, Office of the Prosecutor and the Registry. Each of the trial chambers was composed of three judges, while the Appeals chamber had five judges, who had to be from different states[ICTR Statute, Art 11].

THE ICTR: IT’S INITIAL JURISDICTION

Under Article 1 of the ICTR Statute, the tribunal had power to prosecute persons responsible for serious violations of International Humanitarian Law[IHL] committed in the territory of Rwanda or of neighboring states by Rwandese citizens between 1st January and 31st December 1994[Para 1,Res, 955]. The ratione materiae jurisdiction of the tribunal was the prosecution of persons charged with genocide, crimes against humanity and serious violations of Article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions of August 1949, for the prosecution of victims of war, and of Additional Protocol II, thereto of June 1977.

SOME FACTORS THAT LIMITED OPERATIONS OF THE ICTR

This part of the article looks at several serious limitations that faced the ICTR which suffocated its success during its operations. These included; limitations in the ICTR Statute, limited international co-operation and support especially from very relevant states, technical limitations like administrative hardships and limited harmony with the Rwandese Genocide laws and trials, shortcomings of the ICTR. Each of these limitations is discussed hereunder.

Limitations in the ICTR Statute

Despite the ICTR Statute having very commendable provisions like Articles 2-4, on the subject matter of jurisdiction, and Article 28 which compelled the International community to cooperate, the Statute has limitations which affected the success of the ICTR in its operations. The statute for instance has provisions such as 1 and 7 which limited the temporal jurisdiction of the tribunal to only 1994.This limitation left some genocide cases uncovered, for it is seen, that the genocide began way before 1994, and even went on thereafter. The provisions especially undermined the tribunal’s capacity to address the offences of conspiracy and incitement to commit genocide, which in turn undermined reconciliation as the victims were seen not to get proper justice.

Limited International Support and Co-operation

The ICTR during its tenure, entirely depended on global support and co-operation for everything; funds, personnel, equipment, and above all, apprehension of the suspects. Antonio Cassese explained this better

Our tribunal is like a giant who has no arms and legs. To walk, he needs artificial limbs. These artificial limbs are the state authorities, without their help, the tribunal cannot operate [ ICTFY-Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights.[1997] ‘Prosecuting Genocide in Rwanda :The ICTR and National Trials’330 USA, p. 25].

The SC was well aware of this, and therefore heavily provided for state co-operation [Resolution 955, Paragraph 2,Art 28]. The tribunal however, right from its creation faced various serious problems with states. Although a lot of improvement was made, serious problems still remained.

ICTR Poor Relations with Rwanda

Rwanda pledged to work with the tribunal, despite opposing its creation [Alison Des Forges, 1999,p.739].However, the relationship between the two entities remained poor, especially given the fact that, on top of fresh disagreements the original causes of the misunderstandings still remained[The Sentence of Obed Ruzindana to 25 years Instead of Life Imprisonmet,’Rwanda Attractss Light Genocide Sentence’, The New Vision, Kampala, 25th May 1999 p, 9]. The disagreement between the tribunal and the Rwandan government stemmed from three objections expressed by Rwanda to some of the proposed provisions of the ICTR Statute[Paul J. Magnella 1997, p.121].First the Rwandese Government wanted the maximum punishment for convicts to be death and not the life imprisonment that was proposed; Secondly, the Government also wanted the temporal jurisdiction of the tribunal to go back up to 1990 instead of the proposed year of 1994 alone, to cover earlier crimes especially since it had been agreed that the genocide was masterminded before 1994; thirdly the Government wanted the tribunal to be based in Kigali so as to be appreciated by the Rwandese population, but the Security Council objected to all Rwanda’s proposals. This was however indeed a very bad start for the ICTR, and the poor /frosty relationship between the two parties still existed up to the time of the ICTR’s closure, in December 2015.

Political Influence by some States

Whereas some states were not so co-operative with the ICTR, others exerted political influence on it. It has already been seen that the tribunal was organized according to the wishes of powerful countries like the United States and France, with Rwanda, the concerned party being largely ignored. Unfortunately it looks as if some of these influential states still meddled with the tribunal. For instance back in the day, the Press hinted that, the said dropping of a case against a former Army officer, was a botched attempt to have him extradited to Belgium to face charges for the murder of ten Belgian UN paratroopers[‘Belgium Blasts Tribunal’,The New Vision, Kampala 1st April 1999,p.12].This can be seen to be a very unfortunate state of affairs. Meddling with the formation of a court is bad enough, but meddling with its independence is a sure way of suffocating justice. No Court can certainly function as a justice entity under such influence.

Technical Limitations and shortcomings

The tribunal began with very serious internal problems. First of all, it was financially strapped; lacking basing equipment like telephones, lacked qualified staff, and was rocked with mis-management, nepotism and corruption [Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights, supra p.39-40] There was a lot of improvement, since,[Alison Des Forges supra p.741],but serious problems still existed; secondly, the distance and division of personnel between Kigali, Arusha and the Hague complicated and slowed communication amongst staff. [Alison Des Forges supra p.740].This in turn slowed down the tribunal’s work, which was one of its most serious shortcomings. Also, a substantial number of positions including senior prosecutorial ones were unfilled for a very long time, which also contributed to the slow speed of the tribunal [Alison Des Forges,1999,p.742].Similarly, potential witnesses for both the prosecution and defence were unwilling to testify, either due to fear of reprisals for those in Rwanda, or lack of valid travel documents for those in exile. This especially affected the defendants, whereby some of them failed to come up with even a single witness [Lawyers’ Committee for Human rights, supra,p. 36].This did not only undermine proper justice, but never allowed the ICTR to expose the full truth about what really happened, something that was a cornerstone to reconciliation

ICTR LEGACY

In the months following the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, the UN Security Council established the ICTR. Just before the tribunal’s halting of operations in December 2015, it delivered its Forty Fifth and final judgment-an appeal ruling against six convictions. The tribunal was not the only body set up to judge those responsible for perhaps eight hundred thousand deaths in a hundred days of killing, but it became the first international court to pass a judgment on genocide [Alastair Leithead’ BBC, 2022]. The tribunal was initially a tiny organization, underfunded, and initially permitted only one small court room and two trial chambers to address possible crimes involving the murder of hundreds of thousands. The first hearing of the tribunal, presided over by Senegalese Judge Laity Kama, took place in a small room with a leaky ceiling with’ a couple of tables, a few dozen chairs, one or two interpreters, and a squad of security guards’. The ICTR also suffered from allegations of corruption and several forcing prominent staff to resign in 1996. It took another five years for the tribunal to really find its footing. This inauspicious beginning notwithstanding, slowly but surely made the ICTR begin to establish itself as a functioning, important and indeed vital institution, growing to peak capacity with more than a thousand staff members, four modern courtrooms, and an annual budget of US 140 million.

The ICTR created jurisprudence that both transformed international law and directly affected state behavior paving way for the establishment of the International Criminal Court [ICC] a permanent court that has since succeeded it. Although the ICTR continued to experience growing pains during the period from 1995-98 when the Rome Statute was being negotiated, its establishment, the enthusiasm of international lawyers and Non Governmental Organizations[NGOs] for their operations, and their ability to overcome both technical and practical difficulties proved that international justice could be successfully undertaken.

CONCLUSION

The ICTR had a profound short-and medium-term effect locally, regionally and internationally. This effect was felt in local, regional and international politics, it flowed through the thousands of people whose lives were touched by the work done by the tribunal, and it resulted in the establishment of new institutions of international criminal justice that have since succeeded the ICTR. Indeed, the establishment of a global tribunal to try the perpetrators of the Rwandese atrocities is indeed commendable. But the suffocating limitations, shortcomings evolving around the ICTR, strongly hindered its chances of success in the sense that the ICTR was entirely not able to reconcile the Rwandese or to protect international peace and security, therefore some of the challenges that faced the ICTR still remained even after its closure. In the long or even short run, the legacy of the ICTR lay in the way it dealt with the challenges it faced while still operational, and the future of mankind on the other hand entirely lies in a strong and effective international legal system.

[1]Daniel Lubowa,LLB [Makerere University, Kampala Uganda], LLM [St. Augustine University of Tanzania, Mwanza,Tanzania], He is a Lecturer of International Law at St. Augustine University of Tanzania and a Ph D in Law Candidate at the Open University of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.