By Samora Ashaba

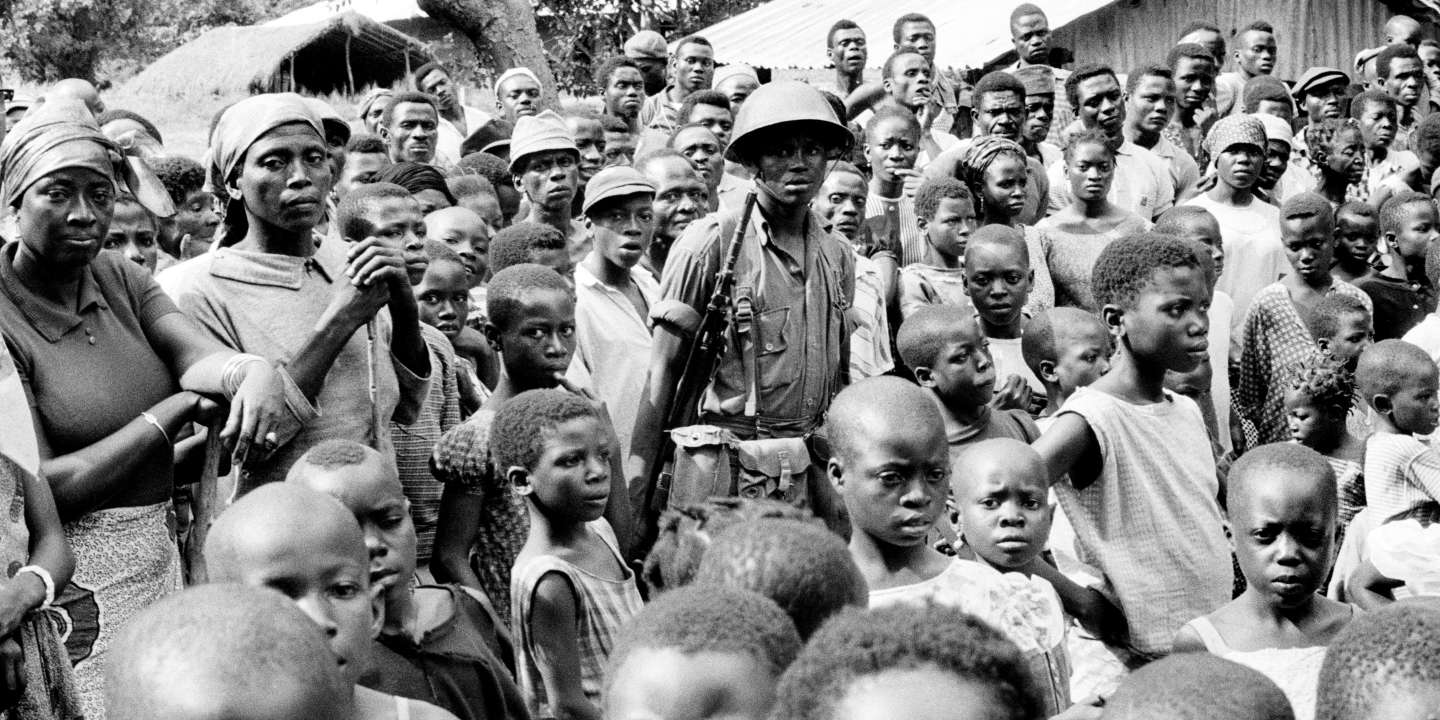

In older wars, large armies needed large open fields or oceans to meet and fight, and these were the frontline spaces.[1]In our current world today technological advancements have spurred a wave of new phenomena impacting International Humanitarian Law (IHL), most notably the emergence of autonomous weapons systems. The Ukrainian military is using AI drones with explosives to target Russian oil refineries, while American AI systems have identified targets for airstrikes in Syria and Yemen. Additionally, Israeli forces labeled around 37,000 Palestinians as suspected militants using an AI targeting system during the early stages of their conflict in Gaza.[2] They are already being incorporated into our militaries and big nations are spending billions on research for these automated weapons. This compels the legal community to urgently address the regulatory framework surrounding these weapons, particularly as warfare itself has shifted from traditional open battlefields due to the rise of autonomous systems.

An autonomous weapon is any weapon system with autonomy in its critical functions, that is, a weapon system that can select (search for, detect, identify, track, or select) and attack (use force against, neutralize, damage, or destroy) targets without human intervention.[3] Hence Identification would then trigger corresponding action through processors or artificial intelligence that would “decide . . . how to respond . . . and effectors that carry out those decisions.”[4] Autonomous Weapons Systems (AWS) can perform the same functions as a combatant in war. However, they lack the essence of humanity, as their decisions are solely based on technical logic rather than moral judgment. Much as there is a race for these kinds of weapons, a number of states approach their use with caution. Even the United States, a global leader in technological advancement in this field, requires that such weapons systems “be designed to allow commanders and operators to exercise appropriate levels of judgment over the use of force.”[5] According to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), these systems are capable of selecting and engaging targets without any human intervention once they have been deployed.[6] While the primary subjects of IHL are the parties involved in armed conflict, we must acknowledge that the principles underpinning IHL—distinction, proportionality, prohibition of unnecessary suffering, and military necessity—are crucial for those who plan, decide, and execute military operations. The Hague Regulations’ Article 1, stipulating the requirement of a commanding person for combatants, provides a compelling justification for the necessity of human involvement in warfare.[7] Therefore, given that our International Laws currently mandate human control over the initiation of hostilities, the emergence of AWS raises fundamental questions about the application of those laws. Isn’t it somewhat ironic that human beings have created machines that could threaten aspects of our intelligence like our humanity and should we have remained committed to traditional methods of warfare? These principles are rooted in our humanity, so how can we rely on machines, which lack any semblance of humanity, to accurately locate, target, and engage in combat while still respecting the principles?

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has emerged as a leading critic of autonomous weapon development, firmly advocating for their prohibition. They assert that “autonomous weapons should be banned and governments should urgently pursue that end,” especially because states are investing billions of dollars into this technology. HRW further contends that these weapons cannot distinguish between soldiers and civilians, raising significant ethical and humanitarian concerns.[8]

Although there is currently no specific treaty or convention in IHL that regulates the use of this new weaponry, IHL stipulates that in situations not addressed by existing treaties, both civilians and combatants are still safeguarded by customary IHL, the principles of humanity, and the imperatives of public conscience.[9] Humanity is essential in addressing armed conflict, as it underpins the core principles upon which IHL is built. Although there is a pressing need for regulation, the international community has not yet reached a consensus on the governance of AWS. The UN Convention on Conventional Weapons features a special amended protocol[10], overseen by the Group of Governmental Experts. However, their latest meeting concluded without significant progress on AWS, as they couldn’t agree on essential regulatory safeguards. Consequently, the draft report[11] did not succeed in establishing a viable legal framework.

In September 2020, during the 75th meeting of the United Nations General Assembly, Pope Francis remarked, “New forms of military technology, such as lethal autonomous weapons systems, irreversibly alter the nature of warfare, detaching it further from human agency.”[12] I believe our humanity is our greatest asset in IHL and in how we engage during armed conflicts. If we remove this essential element from our decision-making process in warfare, it poses a significant threat to the very laws we have established to govern these situations.

The philosophy of Social Darwinism posits the notion of “survival for the fittest” suggesting that certain individuals rise to power in society due to inherent superiority. With World leaders like Vladimir Putin asserting the notion that excelling in AI will dominate the globe, I can’t help but question who will get to us first; those who aspire to rule over us or the robots themselves. AI showcase our remarkable capabilities as a species, but we must not overlook the significant loopholes that require attention. Human beings have a natural affinity to conflict so I believe as states and citizens of the world we need to regulate these weapons before a tragedy meets us at our door step.

[1] Saskia Sassen, When the City Itself Becomes a Technology of War, 2010.

[2] Nick Robins-Early, “AI’s ‘Oppenheimer Moment’: Autonomous Weapons Enter the Battlefield” The Guardian (July 14, 2024).

[3] Neil Davison, ‘A Legal Perspective: Autonomous Weapon System Under International Humanitarian Law’ (International Committee of the Red Cross 2024).

[4]Christof Heyns, Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, Report, 39, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/23/47 (Apr. 9, 2013).

[5] Department of Defense, DOD Directive 3000.09, Autonomy in weapon Systems 3(a) (2012).

[6] ICRC, Autonomous Weapons Systems: Implications of increasing Autonomy in the Critical functions of Weapons (ICRC 2020) 8.

[7] Hague Regulations (IV), RESPECTING THE LAWS AND Customs of War on Land, 18th October 1907.

[8] Human Rights Watch, Losing Humanity: The Case Against Killer Robots (Human Rights Watch 2012).

[9] Additional protocol I, Article 1(2), Additional Protocol II, the preamble.

[10] CCW Amended Protocol II.

[11] CCW_GGE1_2023_CRP.2_with Format Correction.Pdf (Google Docs) <https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QxdviHdL8d3CfoAVGuKLydyS0vNTr_-t/view>.

[12] Pope Francis, ‘The Future We want, the United Nations we need: Reaffirming our collective Commitment to Multilateralism – Confronting COVID 19 through effective multilateral action’ (United Nations General Assembly, New York, 25 September, 2020) https://bit.ly/3kQ2tum